the refusal of self in the context of a foucauldian lens and black european identity

this essay placed me in the top 10% of enteries in the cambridge essay writing competition but didnt win any prizes so now i have the freedom to share it wit y'all lol

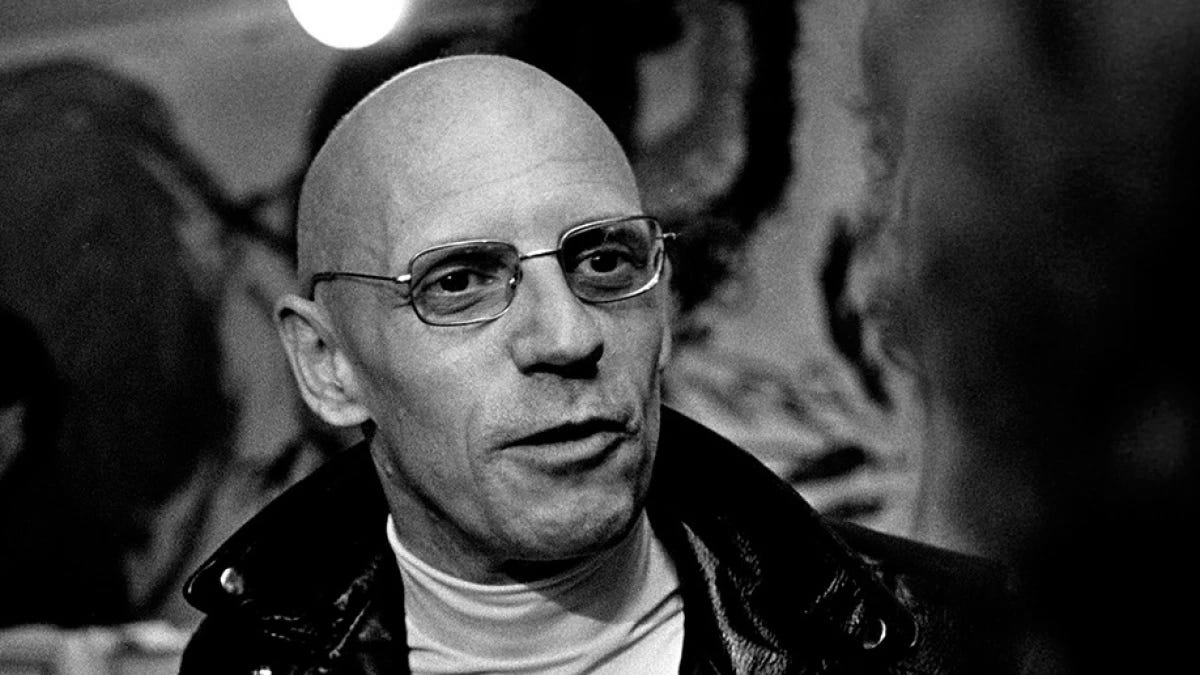

prompt: “The target nowadays is not to discover what we are, but to refuse what we are.” – Michel Foucault (1926-1984) What would we be refusing and why should we refuse it?

Is what we are simultaneous to what we believe to be truthful to our internal identities or a mere fabrication of our livelihoods in an effort to please certain counterparts who slip into the slope of what's expected in societal conventions? The foundation of a Black British identity is a signal between ones African or Caribbean culture in alignment with their experiences as a black person living in Britain. This duality produces not a fixed or singular self, but an identity in flux; negotiated at the intersection of memory, resistance and adaption.

It is within this framework that Foucault's assertion becomes sharply relevant. In a society where blackness has so often been defined externally, through the legacies of empire, institutional racism and cultural stereotyping, the act of refusal is not one of denial, but of reclamation: a strategic rejection of imposed definitions in favour of self-authored subjectivity.

Afua Hirsch in her book ‘Brit(ish) - On Race, Identity and Belonging’ states “If you are poor, and black, with an African surname and a community of poor, black immigrants around you, parents who are not equipped to guide you, a school which expects nothing from you, except a life of crime or low-paid, unskilled labour – because of your race and class – and older children who offer you quick solutions to your safety, by joining gangs, then becoming a lawyer, say, takes something special”. She argues that the premise of what it is to identify as a Black British person is not solely dependent on the occurrences of personalised culture and upbringing, but is, however, constructed through external organisations, social negligence and societal expectations of those who adhere to a black identity. In other words, what's expected of us is what will prevail due to the development of stereotypical ideologies, racism and systematic oppression. In saying that, the ability to negate the stereotypes attached to ones name by [“becoming a lawyer”] or anything other than what’s set in stone by racists, not only derails the hateful nature linked to the labels given to us, but actively refuses them thus supporting the idea that ‘what we are’ is what society expects us to be and breaking away from that is the dismissal of negative attributes given to you over something you cannot control.

The formation of the contemporary Black British identity can be heavily attributed to the history of British Colonialism. Through the British Empire’s expansion to Africa and the Caribbean between the 16th and 20th century we can conclude that the exploitation of enslaved Africans paired with the forced migration of populations and the systematic dismantling of indigenous cultures, aided to the creation of a global racial hierarchy which established racialised identities. As Catherine Hall mentions in Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Migration (2002), “Colonialism is not a separate, distant, or past history but is deeply embedded in the structures of modern Britain and in the ways we construct our sense of identity and belonging.” Applying this, we could argue that British colonialism is not something that's relegated to history but is rather the foundational element in understanding contemporary British identity and the racial dynamics that come along with it. The long-standing effects of colonialism, particularly to race and empire, continue to shape modern British society, with the inclusion of Black British people today.

Foucault's theory is heavily suggestive of our external identities (or internal identities) being the result of the constructional expectations provided to us by the judgemental society we all live in. Through breaking away from the idea that self-discovery is the result of enlightenment thinking ( the idea that through studying ourselves whether it’s from science, philosophy, psychology we can discover our true nature ), he implies that we are all constructed and not discovered which could be cultivated and idealised through historical systems of power and knowledge. Linking this to Hirsch’s quote, historically, the idea of a being a ‘Black-Brit’ is regularly seen as being in direct opposition to the conventions of British normality. By looking at the colonial history of Britain, we can still view the way in which British Imperial ideologies still trickle down in the lives of African and Caribbean immigrant households. A common misconception is that colonialism was primarily the conquering of another country physically; but it was also about implementing a believed hierarchy, one which benefited the lives of colonisers and negatively impacted natives by mentally gaslighting them into thinking they were uncivilised and immoral. This is a topic Frantz Fanon touches upon in his book Black Skin, White Masks (1952) where he essentially provides a psychoanalytical point of view on how British colonialism affected the self-perception of black people and their standards of what they deem as pure and moral. In this book he states, “the colonised is elevated above his jungle status in proportion to his adoption of the mother country’s cultural standards’” arguing that through abandoning one’s identity and adopting the colonisers culture is the way to succession and being recognised as somewhat ‘civilised’.

Amidst the years of seizing and manipulating the prospects of African and Caribbean nations, the British Empire succeeded in creating psychological conflicts within the black community. One of those conflicts being internalised racism. In an effort to appeal white counterparts, it’s not uncommon to hear about the disregard of one’s true identity in the pursuit to feel like they belong. From skin bleaching to hair relaxation, there's no doubt surrounding the shame of what it means to be black for some people not only externally but within your own community. Through colourism and featurism, the effects of colonialism are still ingrained in the minds of those who restlessly view themselves as insignificant and unworthy and I don’t blame them; as being black comes with micro-aggressions and passiveness which couldn’t be made more notable if not for the sly/ inconsiderate comments and attitudes that flourish in today’s society in spite of the efforts made to empower those who possess African features. This unfortunately induces the colonised to focalise themselves in the lens of the colonisers gaze, dehumanising oneself in the efforts to refuse who they are. In bell hooks ‘Killing Rage: Ending Racism’ (1995) she goes on to explain how internalised racism isn't a flaw in one's character, but is however, a survival tactic in a world which shames those for features they were born with and are unable to change. Insulting the skin you were born in may just aid in assimilating you into acceptance as the disregard for the way you look and what features you may possess, helps in supporting the idea that Eurocentric standards of beauty is the dominant standard and the standard most preferred in British society; therefore, recognising that being black and vocalising the fact that having a black identity isn’t idealised, may just contribute towards your inclusion in spaces that are most likely beneficial for you despite the oppression you’ve succumbed to. This further rejuvenates Foucault's belief in the target of today being the refusal of what we are as opposed to the discovery of ourselves.

There comes a point in every black child’s life where we’re taught how to behave in certain spaces. Our skin colour often acts as a barrier to opportunity and self-perception, again, being a result of systemic racism and ingrained social beliefs. Black skin, a visible sight of identity, invites prejudice before any words are even spoken. Code-switching, thus, becomes a tactic necessary to present oneself as more palatable in the effort to avoid any discrimination. This being the reality of four in five (86%) Black British individuals represents the multitude of code switching within the modern Black British home. The process of adopting conventional traits and implementing it into your dialect, or culturally rooted slang shapes the public’s perception of you and your overall success rate whether you’re applying for a job or inserting yourself in a social circle with upheld standards. When individuals become compelled to adjust their speech, mannerisms and appearances to fit within a white-centric norm, the question surrounding whether their true selves are not “professional enough” comes to par, eroding self-esteem issues, cultivating imposter syndrome and distancing oneself from their cultural roots. As cultural theorist Stuart Hall argued in Cultural Identity and Diaspora (1990), identity is not a fixed essence but a constantly evolving position (“production... always in process”). This sheds a light on a psychological perspective of code switching particularly in the lives of black people across the diaspora. The performance that’s attached to code switching and the necessity to portray a more acceptable identity that not only signifies a fractured sense of belonging but also produces a deep-seated pressure to edit one's cultural self in the means to succeed in life’s tumultuous journey.

That being said, some may argue that code switching can also be utilised as being a function of strategy. In looking at notable figures of society’s past, we can direct ourselves towards Marilyn Monroe transition as an example of someone who ‘played the game rather than simply surviving it’. As someone who aligned within cultural ideals of desirability and femininity, she controlled how she chose to be perceived in an overtly misogynistic society as opposed to using code switching to navigate spaces with intention and mastery. In viewing the transformation from Norma Jean Baker to Marilyn Monroe, we can identify her adaptability and ambition in shaping how the world saw her, asserting control over her trajectory. Judith Butler suggests in her theory of performativity that it can be a site of power: “There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very ‘expressions’ that are said to be its results” (Gender Trouble, 1990). By this logic, we can look at identity as not something we reveal, but rather something we decide to construct which aligns with Foucault's original theory. However, unlike Monroe, whose transformation was culturally celebrated, black people who tend to code-switch often face the double burden of adapting to white dominant norms as well as suppressing major parts of their cultural identity in the pursuit to be deemed “professional” or “articulate”. The disparities between the use of codeswitching highlights a critical challenge: what is seen as a renewed reinvention for one group can be viewed and perceived as being inauthentic or deceitful for another. This isn’t just applicable to past starlet’s; we see this through white mediocrity and the affects it has on our modern-day society. Amongst research from UCL’s Institute of Education, it's been discovered that there is a prevalent 4.6% point gap in gaining first-class degrees between Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic students and their white counterparts. This is a clear representation of the troubles surrounding equity in today’s society despite the instances where some may use code switching as a means for acceptance. While it can function as a powerful strategy, it inadvertently remains fraught with racialised assumptions and emotional labour.

With the intent to unravel the constructs that bind identity to fixed cultural, racial or historical expectations, Foucault’s request for us to “refuse what we are” becomes not entirely focused on the act of the abandonment of the self, but a strategic act of liberation. In the context of Black British identity (shaped by colonial legacy, diasporic memory and the gaze of institutional whiteness) this refusal becomes a vital political and cultural manoeuvre. As previously mentioned, code-switching, for instance, is not merely a survival tactic, but a sophisticated navigation of power; a way of refusing society’s singular story attached to every Black British person that roams the country. When examined through this Foucauldian lens, it becomes clear that the quest is not to find a definitive Black British identity, but to challenge the very structures that demand a defined identity. As such, the refusal becomes a reclamation: of voice, of narrative and of possibility. To be Black and British in today's world is to exist in motion. Unfixed, uncontained and unconstrained by what has been dictated.

sources in case anyone cares:

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/postgraduate/masters/modules/asiandiaspora/hallculturalidentityanddiaspora.pdf

https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/16147204.Afua_Hirsch

“ 4.6% point gap ” -https://www.ucl.ac.uk/students/sites/students/files/degree_outcomes_statement.pdf

https://archive.org/details/civilisingsubjec0000hall/page/n3/mode/1up

https://www.j-humansciences.com/ojs/index.php/IJHS/article/view/34933

https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/28359/chapter-abstract/215237149?redirectedFrom=fulltext

https://www.voice-online.co.uk/news/uk-news/2023/10/09/black-gen-z-under-pressure-to-code-switch-at-work-study-finds/

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/postgraduate/masters/modules/asiandiaspora/hallculturalidentityanddiaspora.pdf (Used for insight on the injustices faced by non-whites)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/192305.pdf?casa_token=mzNRbnH9Ng0AAAAA:qiQAwkUwhWaD4tF1VZycrZ4zIrfGRk9mL0UpVL6jB1OufA1U7tKKKjYfwK9MQs18n9RS4FRxvDIzA1B8XCd6-s_M4a45H8X3YwDOJjsn3TjuY0b8GXXp

Books & Author's References:

Afua Hirsch - Brit(ish) - On Race, Identity and Belonging (2018)

Judith Butler - Gender Trouble (1990)

Stuart Hall - Cultural Identity and Diaspora (1990)

Catherine Hall - Civilising Subjects: Metropole and Colony in the English Migration (2002)

bell hooks - ‘Killing Rage: Ending Racism’ (1995)

Frantz Fanon - Black Skin, White Masks (1952)